What Brings Fame?

by Mel Gilden

You never know about fame, do you? You paint a picture you think is pretty good and all viewers just shrug. On another occasion you have nothing to do for an hour or two and you kind of splash something together. Suddenly you are the new Picasso. An interviewer once asked Paul Simon why some of his albums sold better than others. Mr. Simon answered with one of the smartest things anybody ever said about art: "Sometimes people want to hear what you have say and sometimes they don't."

True enough. And usually — often? always? — you don't know going in which it will be. After all, as one of my friends remarked, "Nobody makes a bad piece of art on purpose." Well, maybe. But that's another discussion.

As a corollary to my friend's statement, just wanting to be rich and famous and being willing to work in that direction doesn't mean that either riches or fame will come to you. Committing crimes might help, at least with the fame part — murder seems to be a shortcut — but even that is no guarantee.

Herewith, a few examples:

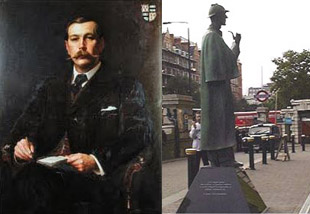

When nobody showed up to see Arthur Conan-Doyle in his capacity as a doctor, he spent the empty hours writing stories about Sherlock Holmes — just hoping to kill time and perhaps make a few pounds into the bargain. He had no way of knowing that he had invented the most famous literary detective of all time. But his troubles were only beginning. Holmes became so famous that Conan-Doyle tired of the character long before the public did. As it turned out, the public never did tire of Holmes. People are still churning out new stories about him. Another surprise for Mr. Conan-Doyle was that when he attempted to write big historical novels like The White Company, stories that were much closer to his heart, nobody wanted to read them. It was the major frustration of his life.

When nobody showed up to see Arthur Conan-Doyle in his capacity as a doctor, he spent the empty hours writing stories about Sherlock Holmes — just hoping to kill time and perhaps make a few pounds into the bargain. He had no way of knowing that he had invented the most famous literary detective of all time. But his troubles were only beginning. Holmes became so famous that Conan-Doyle tired of the character long before the public did. As it turned out, the public never did tire of Holmes. People are still churning out new stories about him. Another surprise for Mr. Conan-Doyle was that when he attempted to write big historical novels like The White Company, stories that were much closer to his heart, nobody wanted to read them. It was the major frustration of his life.

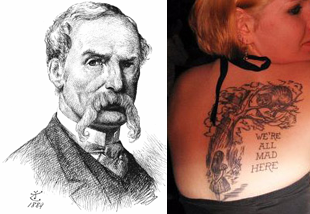

And then there was Sir John Tenniel. During the second half of the nineteenth century he was the go to guy for political cartoons, advertising, and illustrations of any kind. I wonder what his attitude would have been if he'd known that a hundred years after his death the only thing he would be remembered for, if he was known at all, would be for illustrating a fantasy novel, written by a church deacon, about a little girl exploring a place called Wonderland.

And then there was Sir John Tenniel. During the second half of the nineteenth century he was the go to guy for political cartoons, advertising, and illustrations of any kind. I wonder what his attitude would have been if he'd known that a hundred years after his death the only thing he would be remembered for, if he was known at all, would be for illustrating a fantasy novel, written by a church deacon, about a little girl exploring a place called Wonderland.

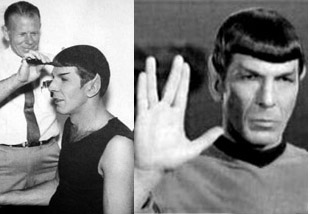

Much closer to our own time, but just as amazing, is the fame of a little science fiction TV show called Star Trek. It first went on the air in 1966, and during the three-year run the writers postulated a lot of future-history that occurred during the 1990s. I'm sure that to the writers 30 years seemed like an adequate buffer between reality and a made-up future. But well into the new millennium interest in Star Trek is still going strong and fans have to ignore the missing Eugenics Wars.

And then there is Trek's most famous character, Mr. Spock. One can only imagine Leonard Nimoy's first reaction to being shown the makeup he was supposed to wear. Bangs? Pointed ears? Heavy sigh. Well, at least it's a week's work. I'm sure that if somebody had told him that 50 years after the fact Spock would still be beloved, he would have thought you were crazy.

And then there is Trek's most famous character, Mr. Spock. One can only imagine Leonard Nimoy's first reaction to being shown the makeup he was supposed to wear. Bangs? Pointed ears? Heavy sigh. Well, at least it's a week's work. I'm sure that if somebody had told him that 50 years after the fact Spock would still be beloved, he would have thought you were crazy.

But you never know, do you?